Moving Averages: Complete Guide to Trend Identification, Bands, Envelopes, and Breakout Channels

Master moving averages from core smoothing mechanics to advanced volatility tools. Learn SMA vs EMA, crossover signals, whipsaws, envelopes, Bollinger/Keltner/STARC bands, Donchian breakouts, and how institutions confirm trends and filter false signals.

Introduction To Moving Averages: Institutional Trend Identification Framework

Moving averages reduce noise.

They do not predict the future.

They simplify market structure so trend direction becomes easier to see, measure, and follow.

Markets contain constant distortion: liquidity shocks, headline spikes, emotional reactions, and short-term chop. Moving averages smooth those oscillations and create an equilibrium reference point that institutions use to answer practical questions:

- Is the market trending or ranging?

- Is momentum strengthening or weakening?

- Is price behaving above or below equilibrium?

- Are we seeing confirmation or just noise?

This guide explains:

- The core smoothing mechanism and why it works

- SMA vs EMA vs weighted and Wilder-style smoothing

- Period selection: speed vs reliability trade-offs

- Lag and why confirmation always comes late

- Price cross signals and MA crossover systems

- Whipsaws in sideways markets and how professionals filter them

- Envelopes (fixed %) and why volatility breaks them

- Bollinger, Keltner, and STARC bands for volatility context

- Band contraction/expansion and bandwidth confirmation

- Donchian channels for breakout and trend continuation logic

Moving averages create clarity.

Clarity enables discipline.

Purpose of Moving Averages: Reducing Noise and Revealing Trend Structure

One of the central functions of moving averages is to reduce the impact of short-term price fluctuations. Financial markets are inherently volatile, and individual price movements may reflect temporary imbalances rather than meaningful directional change. Without filtering, these fluctuations can make it difficult to distinguish between genuine trend development and random variation.

Moving averages address this challenge by calculating the average price over a specified period and updating that value continuously. This process produces a smoother curve compared to the raw price series. Instead of reacting to every minor movement, traders can observe the broader trajectory of the market.

This smoothing effect is particularly important because short-term oscillations can mislead decision-making. Rapid movements often result from emotional reactions, sudden news, or short-term liquidity shifts. Moving averages dampen these effects, allowing analysts to focus on sustained directional movement rather than temporary distortions.

Many successful professional investors and technical analysts use moving averages as a core component of their strategy. These tools help determine when trends are strengthening, weakening, or reversing. Markets that exhibit persistent directional movement benefit especially from moving average analysis, as smoothing reveals structural momentum that might otherwise be obscured.

The key is not prediction.

It is structure recognition.

And structure recognition is the basis of trend-following discipline.

Statistical Validation: Why Moving Average Signals Persist in Professional Use

Moving averages are not just chart folklore. Academic research has examined their usefulness extensively, and multiple studies have shown that moving average rules can contain measurable information under certain conditions. That does not mean they guarantee profits, but it does mean they are more than random visual decoration.

A landmark study by Brock, Lakonishok, and LeBaron (1992) tested simple technical trading rules — including moving average signals — and found evidence of non-random structure in price behavior. Later work across different markets and time periods provided additional support, while also highlighting that results vary based on regime, transaction costs, and the definition of “signal.”

The most important practical takeaway is not “moving averages predict prices.”

It is: moving averages can help summarize trend conditions in a way that is statistically defensible when applied consistently and paired with risk control.

Professionals accept the conditional nature of the edge. Moving averages tend to perform best when trends persist long enough for smoothing to matter. In choppy regimes, the same tools degrade because the market is not producing a trend worth following.

This is why institutions use moving averages as a filter, not a prophecy. They use them to confirm direction, align timeframes, and reduce decision noise.

Moving averages do not eliminate uncertainty.

They make uncertainty easier to manage.

Core Mechanism: What a Moving Average Actually Represents

A moving average is the average price of an asset over a defined number of past periods. Instead of treating each price observation as equally important in decision-making, the moving average compresses a window of history into a single evolving reference value.

For example, a 20-day moving average summarizes the last 20 closes. Each new day, the newest price is added and the oldest observation is removed (or down-weighted, depending on the method). This rolling update is why it is “moving.”

This matters because markets are noisy. A single candle can reflect a temporary imbalance or a headline reaction that does not represent true directional pressure. By averaging over time, the indicator reduces the influence of that noise and reveals whether price has been rising, falling, or drifting sideways.

The slope becomes meaningful:

- Rising MA → recent prices are generally higher than earlier prices

- Falling MA → recent prices are generally lower

- Flat MA → equilibrium, consolidation, or uncertainty

That slope is why moving averages are used as “trend lines that compute themselves.” They provide a consistent, repeatable trend reference without requiring subjective line drawing.

The trade-off is embedded in the design: more smoothing means more stability — but also more delay.

Moving averages do not react instantly.

They confirm direction gradually.

SMA: The Baseline Smoother (and Why It Still Matters)

The simple moving average (SMA) is the most straightforward form of smoothing. It calculates the arithmetic mean of the last N prices. Every data point inside the window has equal weight, which makes SMA stable and easy to interpret.

That equal weighting is both a strength and a limitation. It creates strong smoothing, which can improve clarity in trend identification. But it also causes SMA to react slowly when the market shifts, because older data continues to pull the average toward past conditions even when price has already changed.

Professionals still use SMA because:

- It is widely watched (self-reinforcing behavior is real)

- It provides clean, stable equilibrium reference

- Long SMAs (50/200) often map to institutional “trend regime” framing

Common uses include long-term trend filters (e.g., price above/below 200-day), support/resistance framing, and system rules that demand simplicity and repeatability. SMA also acts as a neutral benchmark for comparing faster averages like EMA.

SMA is not “worse” than EMA.

It is slower by design.

And sometimes slow is the point.

EMA and Weighted Methods: Faster Response Without Losing the Smoother

The exponential moving average (EMA) modifies SMA’s equal-weight structure by emphasizing recent prices more strongly. Instead of abruptly “dropping off” old data, EMA fades older influence gradually. This reduces the drop-off distortion and increases responsiveness.

EMA uses a multiplier based on period length:

- Weight = 2 ÷ (N + 1)

The result is a smoother that reacts faster to trend changes while still filtering noise. This is why EMA is embedded inside many institutional indicators, including MACD and a large family of momentum/trend tools.

Weighted moving averages (like LWMA) also increase the importance of recent data, typically using linear weighting. These methods sit between SMA and EMA in spirit: they reduce lag compared to SMA, but the exact behavior depends on weighting design.

The practical trade-off remains constant:

- Faster averages → earlier signals, more whipsaws

- Slower averages → later signals, fewer false flips

Institutions often solve this by using layers: a slower MA to define regime, and a faster MA to time decisions inside that regime.

EMA is not magical.

It is simply a better balance of speed and stability for many markets.

Lag and Confirmation Delay: Why Moving Averages Never Catch the Exact Turn

Moving averages are inherently lagging indicators. That is not a flaw — it is the cost of smoothing. Because the MA is built from historical data, it cannot reflect a new regime until enough new information enters the window.

This is why moving averages confirm trends rather than predict them. When a reversal begins, the moving average may remain flat or continue in the old direction for a period of time. The indicator only turns once the weight of new prices overwhelms the influence of older prices.

Professionals accept this because:

- catching the exact bottom/top is not the goal

- confirmation reduces false entries

- the “middle” of trends is where trend systems live

The objective becomes capturing sustained movement, not maximizing precision. In a trend-following framework, missing the first part of the move is acceptable if it reduces false signals and protects capital.

Lag is the price of clarity.

And clarity is often worth paying for.

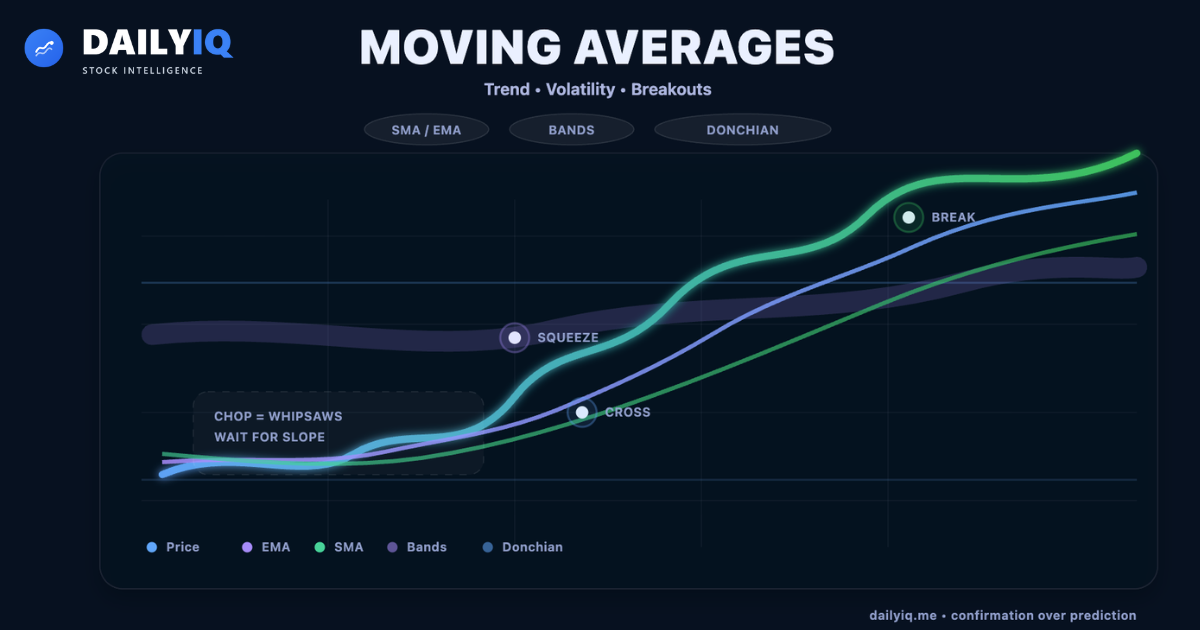

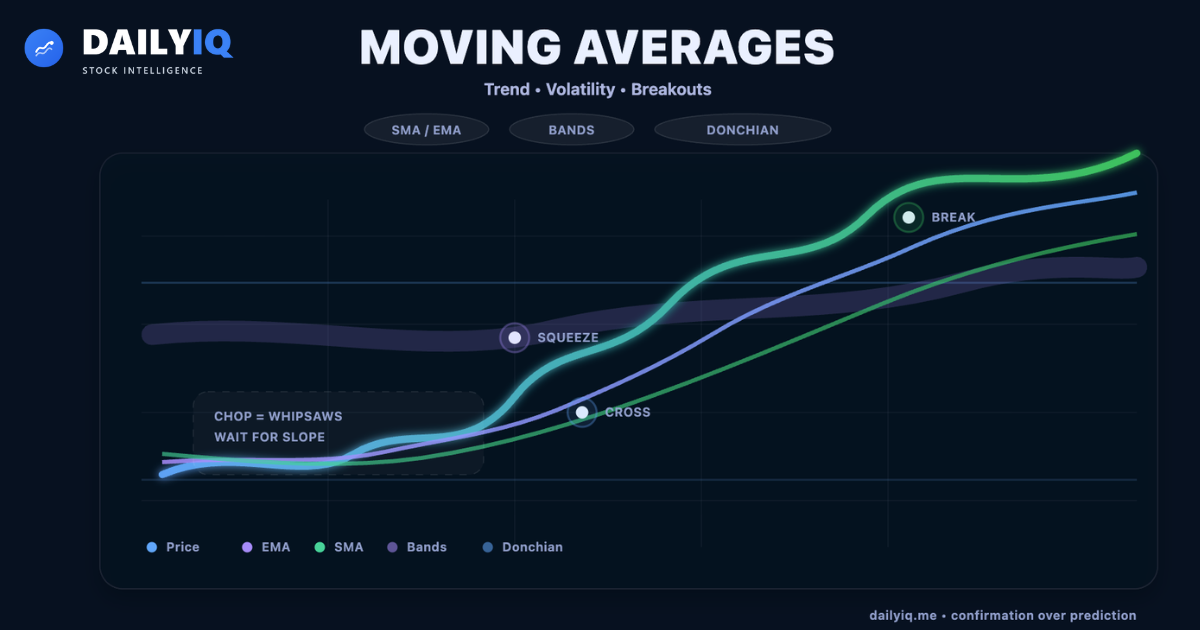

Crossover Systems: Price Crosses and MA Crosses as Structural Signals

Moving averages generate two broad categories of signals.

1) Price cross signals

- Bullish: price crosses above the MA

- Bearish: price crosses below the MA

These signals treat the MA as an equilibrium line. Price behavior around the average helps classify regime and momentum.

2) Moving average crossovers

- Bullish: short-term MA crosses above long-term MA

- Bearish: short-term MA crosses below long-term MA

Crossovers attempt to measure whether recent prices are strengthening or weakening relative to longer-term structure. The classic examples are 50/200 (“golden cross” / “death cross”), but professionals often customize lengths to fit timeframe and volatility.

Crossovers work best when trends persist. They fail most often when markets chop sideways and repeatedly rotate around equilibrium. This is why crossover strategies are typically paired with filters: volatility context, trend strength measures, higher-timeframe alignment, or confirmation rules.

Crossovers are not predictions.

They are mechanical recognition of momentum shift relative to a baseline.

That recognition can be useful — if the market is actually trending.

Whipsaws in Sideways Markets: The Core Failure Mode (and How to Filter It)

The main weakness of moving averages is exposed in non-trending conditions. When price rotates inside a range, it crosses the moving average frequently. Short and long averages also cross each other repeatedly. The result is a sequence of false signals and small losses — the classic whipsaw problem.

This happens because moving averages require directional persistence. Without a sustained push, the average becomes a “magnet” rather than a trend guide. Many traders mistakenly treat every crossover as meaningful even when the market is structurally range-bound.

Professionals reduce whipsaws by adding context:

- Use a higher-timeframe MA to define regime first

- Require slope thresholds (avoid flat MA conditions)

- Use volatility filters (ATR, bands, bandwidth expansion)

- Demand close confirmation or multi-bar persistence

- Use envelopes/bands so signals require meaningful distance

In other words: stop trading moving averages in an environment where moving averages cannot work.

Whipsaws are not a mystery.

They are the predictable result of trend tools applied to non-trend structure.

Envelopes: Fixed-Percent Channels (and Why Volatility Makes Them Fragile)

Moving average envelopes plot two lines above and below a moving average at a fixed percentage distance. For example, a 20-day MA with a ±1% envelope creates a channel where price is considered “extended” near the outer bands.

Envelopes are useful for two reasons:

- They help visualize extremes relative to equilibrium

- They filter small crossings near the MA that would otherwise trigger noise signals

The problem is volatility. A fixed ±1% band does not adapt when the market’s typical movement expands or contracts. In calm conditions, the envelope can be too wide and fail to identify meaningful extremes. In high volatility, it can be too tight and get hit constantly.

This limitation is exactly why volatility-adjusted bands became dominant.

Envelopes create structure.

Volatility decides whether that structure is usable.

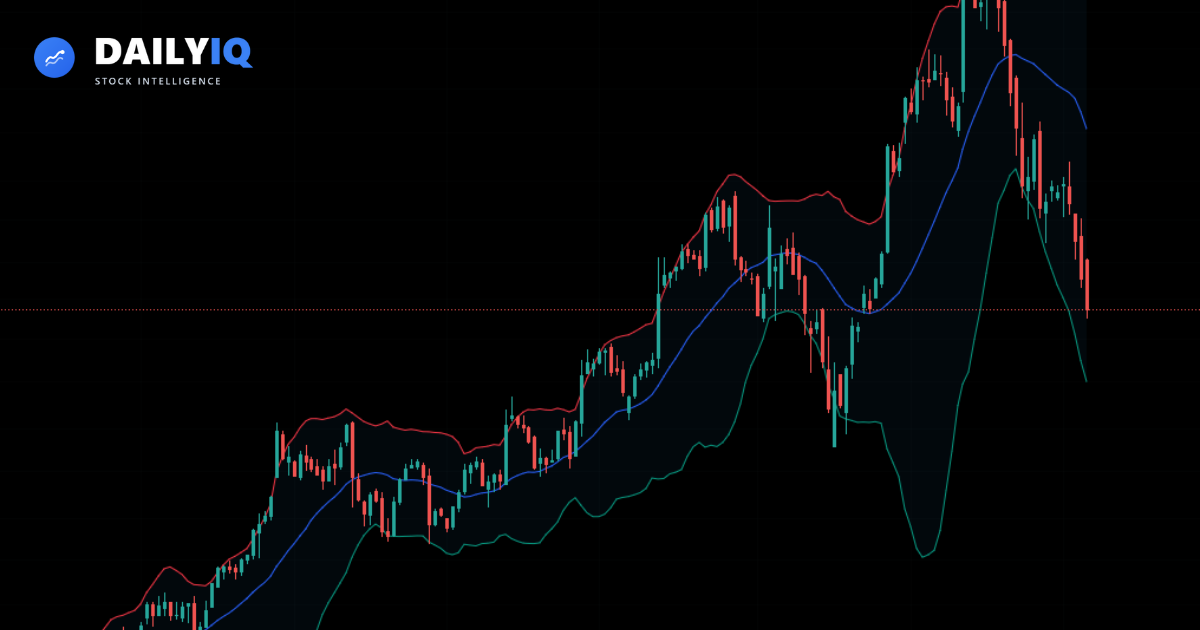

Volatility Bands: Bollinger, Keltner, and STARC as Adaptive Equilibrium Frameworks

Volatility-based bands solve the fixed-envelope problem by expanding and contracting with market conditions.

Bollinger Bands use standard deviation around a moving average (commonly 20-period, ±2σ). Because standard deviation measures dispersion, the bands widen in volatile periods and narrow in calm periods. Contraction often precedes expansion — which is why band “squeezes” are watched for breakout potential.

Keltner Channels use ATR instead of standard deviation. ATR tracks realized range and gaps, producing smoother adaptive channels that many traders prefer in trend-following frameworks.

STARC Bands (Stoller Average Range Channels) also rely on ATR around a moving average. They are frequently used for “extreme” framing — price near upper band can reflect overbought extension, and near lower band oversold extension, depending on regime.

Across all three, the institutional value is the same: bands provide context. They show whether price is behaving normally or abnormally relative to recent volatility. They also help confirm breakouts: a breakout that occurs alongside volatility expansion is structurally healthier than a breakout that occurs with no volatility participation.

Bands do not replace moving averages.

They upgrade them into volatility-aware trend frameworks.

Band Contraction and Bandwidth: How Professionals Spot Compression Before Expansion

One of the most valuable band concepts is compression.

When volatility declines, bands contract. This often happens during consolidation and equilibrium-building phases. Markets tend to alternate between low-volatility compression and high-volatility expansion. That alternation is not a guarantee of direction — but it is a reliable structural rhythm.

Bollinger Bandwidth (the distance between upper and lower band) turns this idea into a measurable indicator:

- Falling bandwidth → volatility contracting, consolidation building

- Rising bandwidth → volatility expanding, trend force increasing

Professionals use bandwidth and squeeze behavior to avoid chasing random movement and to identify when the market is transitioning from “quiet” to “active.” Breakouts from compression zones can be powerful because the market has spent time absorbing order flow, reducing randomness, and building potential energy.

But the key is confirmation. Compression tells you “movement is likely coming.”

It does not tell you which direction will win.

Compression is the setup.

Expansion is the confirmation.

Donchian Channels: Breakout Channels Based on Extremes (Not Formulas)

Donchian Channels define boundaries using recent price extremes rather than volatility formulas.

- Upper band = highest high over N periods

- Lower band = lowest low over N periods

A common setting is 20 periods. When price breaks above the upper band, it signals a breakout beyond recent extremes. When it breaks below the lower band, it signals downside breakout. This method is structurally simple: it defines trend initiation as “new extreme.”

Donchian channels are widely used in breakout and trend-following systems because they align with how trends behave: sustained trends repeatedly print new highs (uptrends) or new lows (downtrends). They are also easy to test and systematize.

Like all breakout frameworks, Donchian signals work best when the market transitions from range to trend. In a choppy range, price can repeatedly tag extremes without follow-through. This is why many professionals combine Donchian channels with volatility context (e.g., bandwidth expansion) or time confirmation rules.

Donchian channels are not fancy.

They are structural.

And structural tools often endure the longest.

Conclusion: How Moving Averages Improve Decision Quality

The primary objective of technical analysis is not certainty. It is structured decision-making under uncertainty. Moving averages remain foundational because they compress noisy market behavior into a cleaner trend framework.

They help you:

- Identify trend direction and regime (up, down, sideways)

- Anchor equilibrium (mean reference and deviation)

- Generate mechanical signals (crosses and crossovers)

- Confirm trend strength through slope and persistence

- Reduce emotional overreaction to short-term volatility

Their limitations are equally important:

- They lag by design

- They whipsaw in ranges

- They require context to avoid false signals

That is why institutional frameworks rarely use a moving average alone. They combine smoothing with volatility awareness (bands), structural extremes (channels), confirmation rules (close/time), and risk control.

Moving averages do not remove uncertainty.

They reduce confusion.

And reducing confusion is often the edge.

Use MAs to Define Regime

Treat moving averages as a trend filter first. Use slope, price position, and higher-timeframe alignment to decide whether a trend strategy even makes sense.

Add Volatility Context

Envelopes, Bollinger/Keltner/STARC bands, bandwidth, and ATR filters reduce false signals by forcing the market to “prove” movement is meaningful.

Respect Whipsaws

Sideways markets are the failure mode. Filter ranges, demand confirmation, size appropriately, and accept that trend systems pay a “noise tax.”

Quick FAQ

Is EMA always better than SMA?

No. EMA is faster, but faster means more noise sensitivity. SMA can be better for long-horizon regime filters where stability matters more than early signals.

Why do moving averages whipsaw so much in ranges?

Because price rotates around equilibrium and keeps crossing it. Trend tools require persistence. In a range, the MA becomes a magnet rather than a guide.

What’s the best way to reduce false MA signals?

Add context: slope filters, higher timeframe alignment, volatility filters (ATR/bands), close/time confirmation, and avoid trading crossovers when the MA is flat.

How do bands help moving averages?

Bands convert a single equilibrium line into a volatility-aware framework. Contraction/expansion and band breaks help confirm whether movement is meaningful.

What’s the point of Donchian channels if I have Bollinger Bands?

Donchian channels define breakouts by new extremes, not by standard deviation or ATR formulas. They’re simpler and often cleaner for systematic breakout rules.

Learn About Investing

These resources can help investors evaluate momentum, volatility, and trend strength when analyzing Moving Averages: Complete Guide to Trend Identification, Bands, Envelopes, and Breakout Channels.

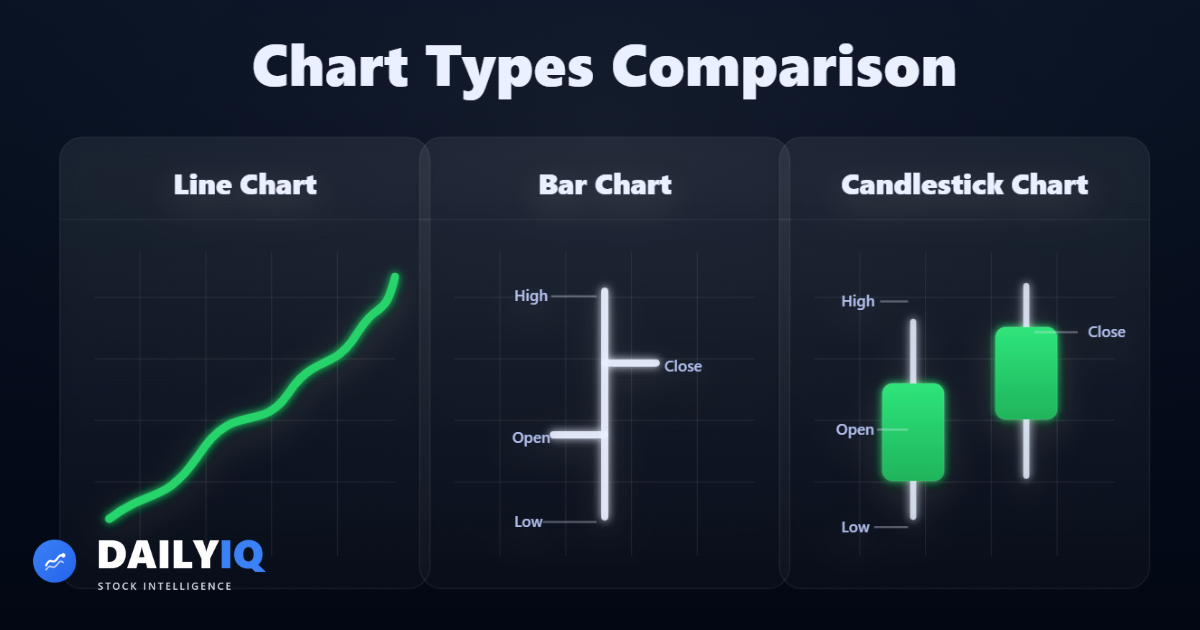

Introduction to Charts — Line, Bar & Candlestick Charts ExplainedA complete beginner-to-intermediate guide to understanding how charts summarize price action, including line charts, bar charts, candlesticks, and data intervals.Technical · 22 min read

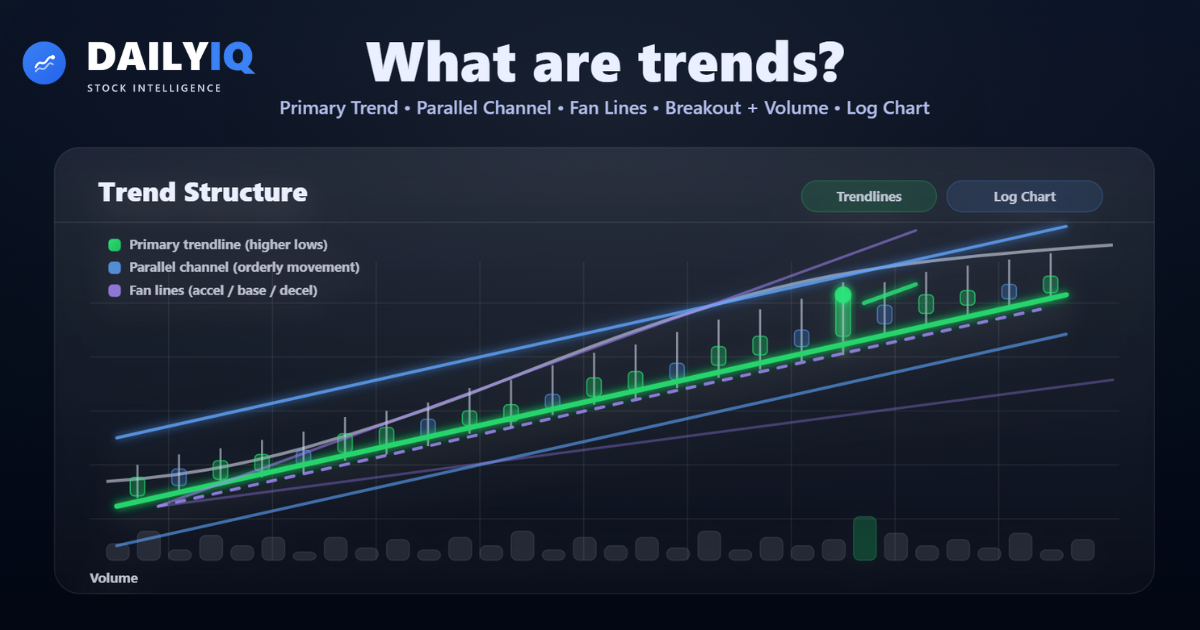

Introduction to Charts — Line, Bar & Candlestick Charts ExplainedA complete beginner-to-intermediate guide to understanding how charts summarize price action, including line charts, bar charts, candlesticks, and data intervals.Technical · 22 min read Trend Lines in Technical Analysis: The Complete Institutional GuideMaster trend lines, accelerating and decelerating structures, channels, log scale, Pitchfork, Gann fans, and professional breakout confirmation.Technical · 22 min read

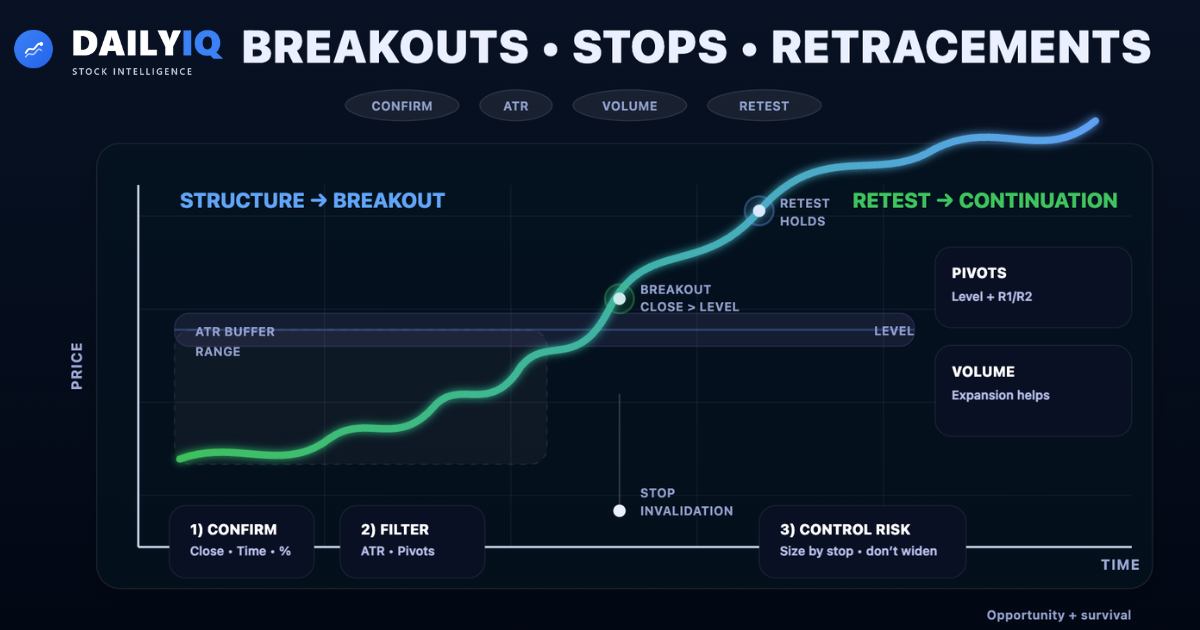

Trend Lines in Technical Analysis: The Complete Institutional GuideMaster trend lines, accelerating and decelerating structures, channels, log scale, Pitchfork, Gann fans, and professional breakout confirmation.Technical · 22 min read Breakouts, Stops & Retracements: The Institutional Trading FrameworkMaster breakout confirmation, volume analysis, volatility filters, ATR methods, pivot techniques, anticipation signals, and professional stop-loss management.Technical · 24 min read

Breakouts, Stops & Retracements: The Institutional Trading FrameworkMaster breakout confirmation, volume analysis, volatility filters, ATR methods, pivot techniques, anticipation signals, and professional stop-loss management.Technical · 24 min read What Is ATR and How to Use ItLearn how the Average True Range (ATR) measures volatility and helps you set smarter stop losses and position sizes.Volatility · 6 min read

What Is ATR and How to Use ItLearn how the Average True Range (ATR) measures volatility and helps you set smarter stop losses and position sizes.Volatility · 6 min read What Are Bollinger Bands and How to Read ThemLearn how Bollinger Bands measure volatility, identify breakouts, and highlight overextended price conditions.Volatility · 5 min read

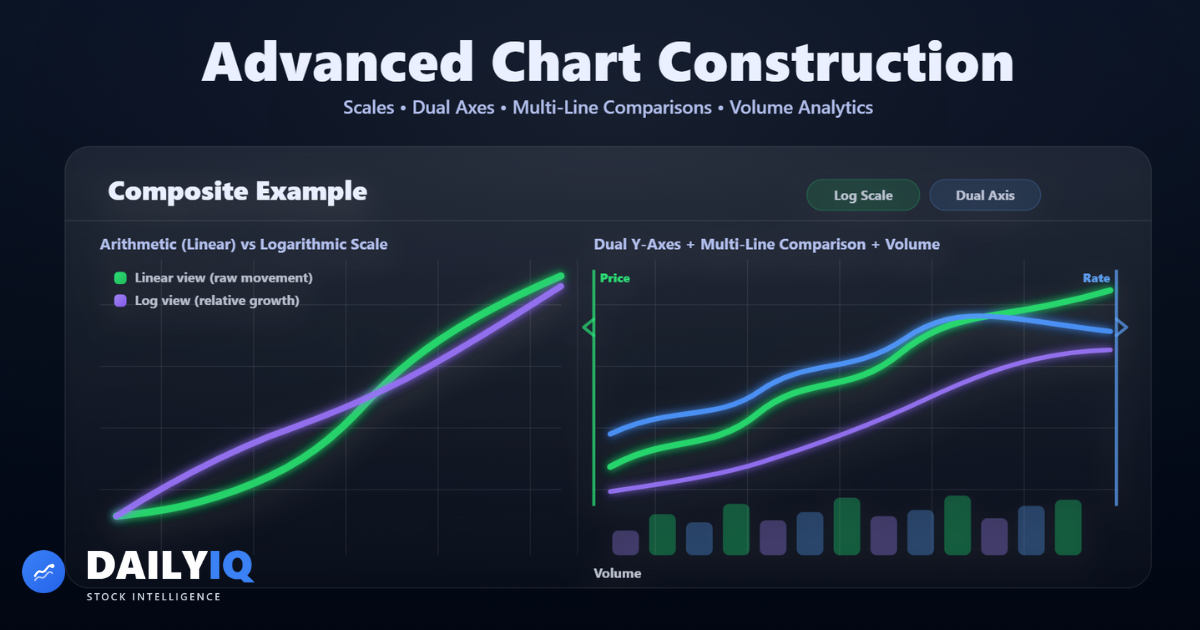

What Are Bollinger Bands and How to Read ThemLearn how Bollinger Bands measure volatility, identify breakouts, and highlight overextended price conditions.Volatility · 5 min read Advanced Chart Analysis: Scaling, Volume, and Comparative Charting ExplainedA comprehensive guide to advanced chart construction including arithmetic vs logarithmic scales, dual y-axes, multi-line comparisons, and volume-based charting techniques.Technical · 22 min read

Advanced Chart Analysis: Scaling, Volume, and Comparative Charting ExplainedA comprehensive guide to advanced chart construction including arithmetic vs logarithmic scales, dual y-axes, multi-line comparisons, and volume-based charting techniques.Technical · 22 min read